Old Town Decatur

Decatur’s oldest community, and oldest property continuously occupied by African Americans, Old Town comprises the original boundaries of the Northwest Alabama city. The first lot was sold in 1821, five years before Decatur was incorporated, and it developed into a predominately white, working-class neighborhood over the next several decades. During the Civil War, it was almost completely destroyed by occupying Union forces, with only two buildings spared: the Rhea-McIntire House and the Dancy-Polk House, which sat next to the rail line and served as headquarters for both Union and Confederate forces. After the war, Decatur’s rail lines were rebuilt and incorporated into the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad, which stimulated economic growth. The city’s population also grew exponentially, as new industrial employment opportunities attracted former slaves and their families to the area. During Reconstruction, as white residents migrated east of the railroad tracks and settled in New Decatur to the south, Old Town re-emerged as a working-class African-American neighborhood. The urban environment that attracted former slaves also provided educational opportunities, and by the early 1900s, Old Town was home to a number of black professionals, including Dr. Willis E. Sterrs, Decatur’s first African-American doctor and the founder of its first hospital.

“During the segregated South, Old Town… was a town where blacks lived primarily and it was contained. They had their own grocery stores, their own restaurants, their own pool halls [and] beauty shops… This is where blacks primarily lived and shopped. They did everything there.”

The eastern portion of Old Town, in particular, evolved over the next several decades into what the Decatur Daily described as “a centerpiece of the Black community and… one of the city’s most vibrant neighborhoods,” its streets lined with grocery stores, diners, dance halls and more. Many minority-owned businesses were located on Bank Street, in Decatur’s oldest business district, particularly in the area surrounding the Old State Bank building. There was also a “thriving and diverse business district” west of the rail line on Vine Street, where black professionals and entrepreneurs worked alongside white and immigrant business owners like the Namie and Shaia families.

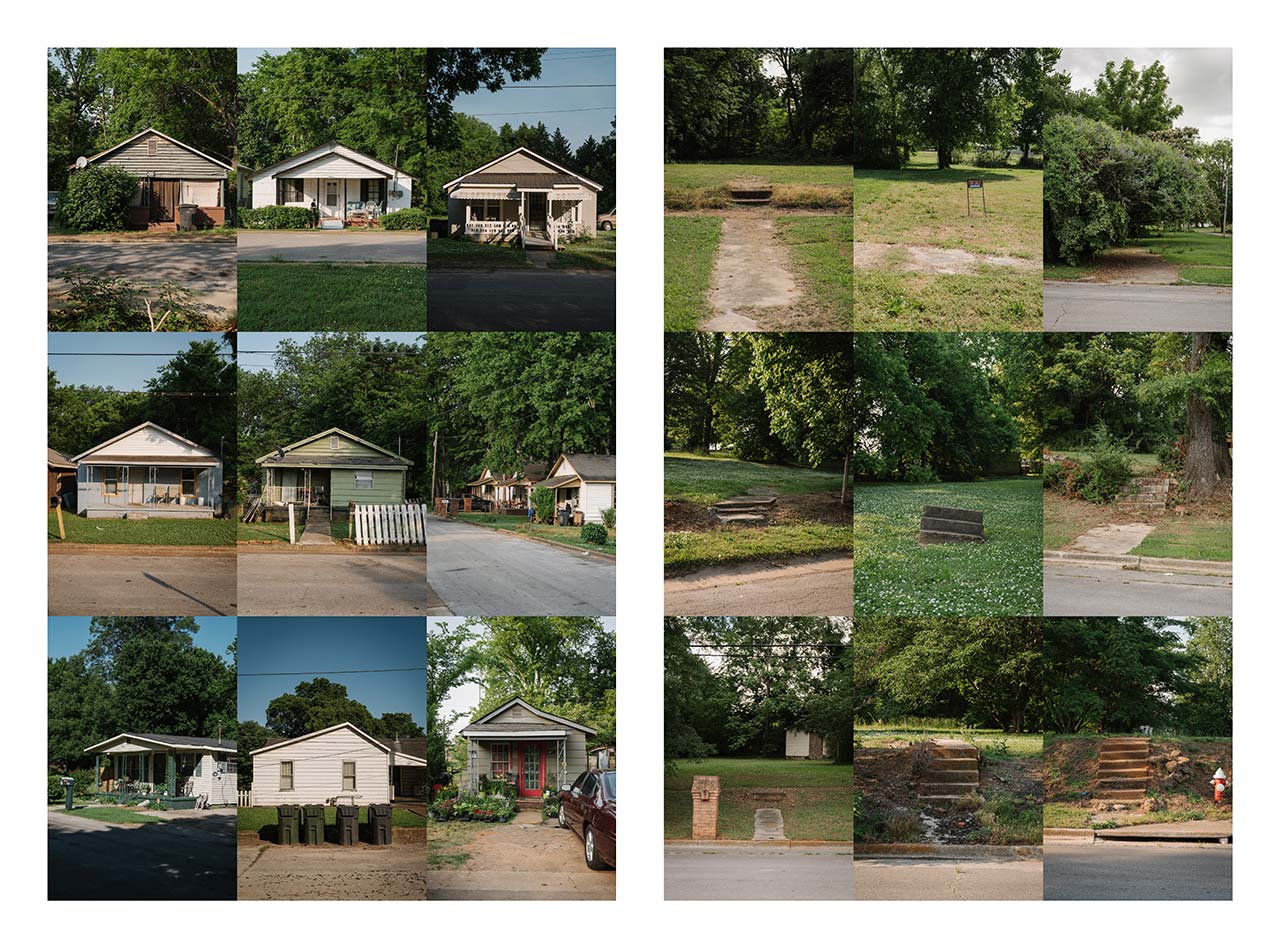

As a result of urban renewal efforts undertaken by the city of Decatur, few physical traces of Old Town’s vibrant legacy remain today. During the 1950s, a large portion of the neighborhood south of Vine Street was cleared to make way for the federally-subsidized Cashin Homes. Over the next several decades, as residents and business owners relocated, older buildings deteriorated. In the 1970s, the city began the Urban Renewal Redevelopment program and most of the remaining structures were razed, leaving behind vacant lots. Reminders of Old Town’s past persist, however, including the W.A. Rayfield-designed First Missionary Baptist Church, with its distinctive towers and stained-glass windows. Meanwhile, Old Town natives like historian Peggy Towns and artist Frances Tate keep the neighborhood’s memory alive, and in 2012 the neighborhood was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

“The bus driver asked me to, you know, give my seat to a white man, so I turned him down. He didn’t make an issue out of it, he could have done anything, and nobody would ever know what happened to me; I was the only black on the bus.”

Hear Etta Freeman’s Story:

“I would like to see Vine Street filled with businesses again, but until that time, we will tell the story. I think that it’s our duty to tell that story; to tell the story about the business owners; to tell the story about the people who sit in these pews; to tell the story.”

Hear Peggy Town’s Story:

“When you think of the Tennessee River, as it flows, your legacy flows, and I think of that bringing unity to the community. All of it works together. That was my concept of using the water from the Tennessee River. The unity that it brings, and we’re trying to create a legacy that will last and flow forever, and the Tennessee River, it never stops flowing.”

Hear Frances Tate’s Story:

“There was a parade here. Over two thousand people turned out with their children and wives for the Klan parade, and all in Decatur, Alabama.”

“This community built itself into something extraordinary and historic because of the efforts of these churches and the people that are in these churches. This community still has the potential and the genius to be something special; it’s just going to require more.”

Hear Her Story:

Hear Their Story: