This Historic Trace

The progression of the Natchez Trace parallels the evolution of the region more broadly. It began life as a migratory animal and Native trading route, part of a larger system of indigenous paths through the southeastern landscape. When European-American settlement started to drift upward from the mouth of the Mississippi and west from the eastern seaboard, the new arrivals to the “Old Southwest,” as Alabama and Mississippi were known, began using the Trace to move around the region. The route connected these new communities to Nashville in the North and New Orleans in the South.

While the original footpaths of the historic Trace only remain intact in a few areas, exploring the old routes reveals a clear social and ecological history of the region. To truly understand the Trace and its place in the region’s history, people need to do more than just explore the signs and stops on the parkway itself. They need to pull off an exit ramp and explore the people and places of the Old Trace, as well.

The “Old Natchez Trace” or “Old Trace” is a historic travel corridor used by American Indians, “Kaintucks,” European settlers, slave traders, and soldiers. Native Americans were the first to utilize the Natchez Trace, ushering in an era of trade and travel through this region that lasted for thousands of years.

In the early 1800s, many farmers and boatmen from the Ohio River regions of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Kentucky traveled north along the Old Trace. Before steam power made river travel easy in both directions, these men floated trade goods down to ports in Natchez and New Orleans. Regardless of where they came from, they were collectively known as “Kaintucks.” After selling their lumber and boats, they would make their way home over land on

the Old Trace. When President John Adams designated the Old Trace as a postal road, it also became a popular place for stands, or inns, who catered to travelers along the increasingly busy route. These stands became safe havens with a place to rest and a meal to eat during the long journey up or down the Old Trace.

While the United States banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, at the same time cotton was beginning its ascent to be the largest export from the United States. To feed the ever increasing demand for cotton, the years from 1830 to 1860 saw a forced migration of slaves from Virginia and the Carolinas southward. Owners and slave traders moved enslaved people in coffles, chaining them together and marching them from one place to another. Nearly one million people were moved along the Old Trace in what has been referred to as the “Slave Trail of Tears.” Often traveling by boat was faster and safer than the arduous trek down the Trace, but it was also more expensive. The Trace became an economic lifeline for the perpetuation of the domestic slave trade.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, stretches of the road fell into disrepair, while other sections became part of the county road system. But the story of the Old Trace does not end there. With the support of the federal government, twentieth century preservationists reimagined the route as a scenic parkway.

To explore the Trace, use the interactive map below. Click on each location for pics & stories.

Explore This Historic Trace

Mhoontown

The Mhoons came to the region from North Carolina in the early 1800s. In 1828, they established a large farm and Methodist church situated near the Old Trace and only a few miles from Colbert’s Ferry, an important crossing point on the Tennessee River. The family eventually relocated to California during the gold rush. However, their influence is still visible in the Mhoontown cemetery where their large family obelisks rise from the ground. The Mhoontown cemetery and church are both still in use at present.

Buzzard's Roost

Originally this site was called Buzzard Sleep. Levi Colbert, a Chickasaw chief and brother of George Colbert, changed the name to Buzzard’s Roost in 1801. Bernard Romans’ Map of 1772 indicated a place called “Chickianooe,” which appears to be a misprint of the Choctaw word “Chickianoce” meaning “buzzards there sleep.”

The Colbert house used the spring as a water source. The house also served as an inn and stand for travelers on the Old Natchez Trace. It took two hours to by horseback between the two Colbert stands.

Buzzard's Roost Covered Bridge

Buzzard Roost Covered Bridge was built over Buzzard Roost Creek in 1860, was 94 ft. long, and located on Allsboro Road; fire destroyed the bridge on July 15, 1972. Before it burned, the Buzzard Roost Covered Bridge was one of the few remaining examples of a traditional covered bridge in Alabama. Alex Bush photographed it in the 1930s as a part of the Historic American Building Survey by the Library of Congress.

Nearby Barton Hall, also known as the Cunningham Plantation, was also surveyed and photographed as a part of the HABS project. Built in 1840, the Greek Revival house is most notable for its unique staircase that ascends in a series of double flights and bridge-like landings to an observatory on the rooftop. It is one of three National Historic Landmarks located in the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area.

Colbert's Ferry

George Colbert, Levi Colbert’s brother, operated a ferry on the south side of the Tennessee River from 1800 to 1819. His stand, or inn, offered travelers a warm meal and shelter during their journey on the Old Trace. Colbert, a member of the Chickasaw Nation, is often mentioned in historic accounts of the Natchez Trace due to the strategic location of his ferry along the river. He played a vital role in developing the post road near his property. He started his ferry and stand services immediately after the US Army improved the Natchez Trace in 1801.

In 1837 Colbert accompanied the major portion of his fellow Chickasaw to the Oklahoma territory during the Chickasaw Removal. His prosperity followed him to Oklahoma; however, it was short lived due to his death in 1839.

The nearby Georgetown Cave overlooks the river and is federally protected as a potential Gray Bat habitat, which could be vital to the preservation of the species.

Threet's Crossroads

One of the best places to explore the Old Trace is on County Road 5 in Lauderdale County. The community of Threet, which is located north of Savannah Highway (Highway 20) is especially rich in historical resources, including a cemetery, dogtrot cabins, and other historic structures. One of the most important features on the road is Threet’s Crossroads, originally known as Russell’s Crossroads, which today is the intersection of County Roads 5 and 8. At one time the community school and local store sat near the church that now sits at the crossroads. One of the earliest families to migrate to the area was the Austins, who came to the region in the early 1800s and owned much of the property around the crossroads. Today they continue to live in the area and the Austin family cemetery remains an active place of burial.

Tom's Wall

Right down the road from Threet’s Crossroads on County Road 8, Tom Hendrix built a memorial to his great-great-grandmother. She lived near the Tennessee River in the 1830s and was forcibly removed to Oklahoma on the “Trail of Tears.” She eventually returned and the monument to her is made of rocks, each one representing a step she took. It took Hendrix more than thirty years to build the memorial.

Bear Creek Mounds

Freedom Hills

Cherokee

Cherokee

John Coffee Memorial Bridge

Tennessee River

Rock Creek Springs

Threet's Crossroads

Austin Cemetery

Austin Cemetery

County Road 660

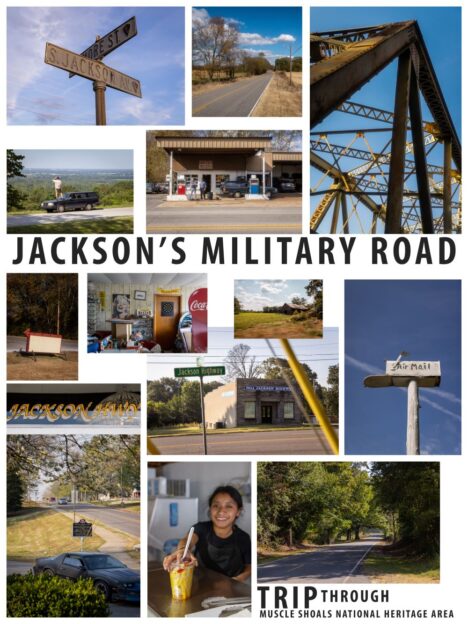

The Modern Trace

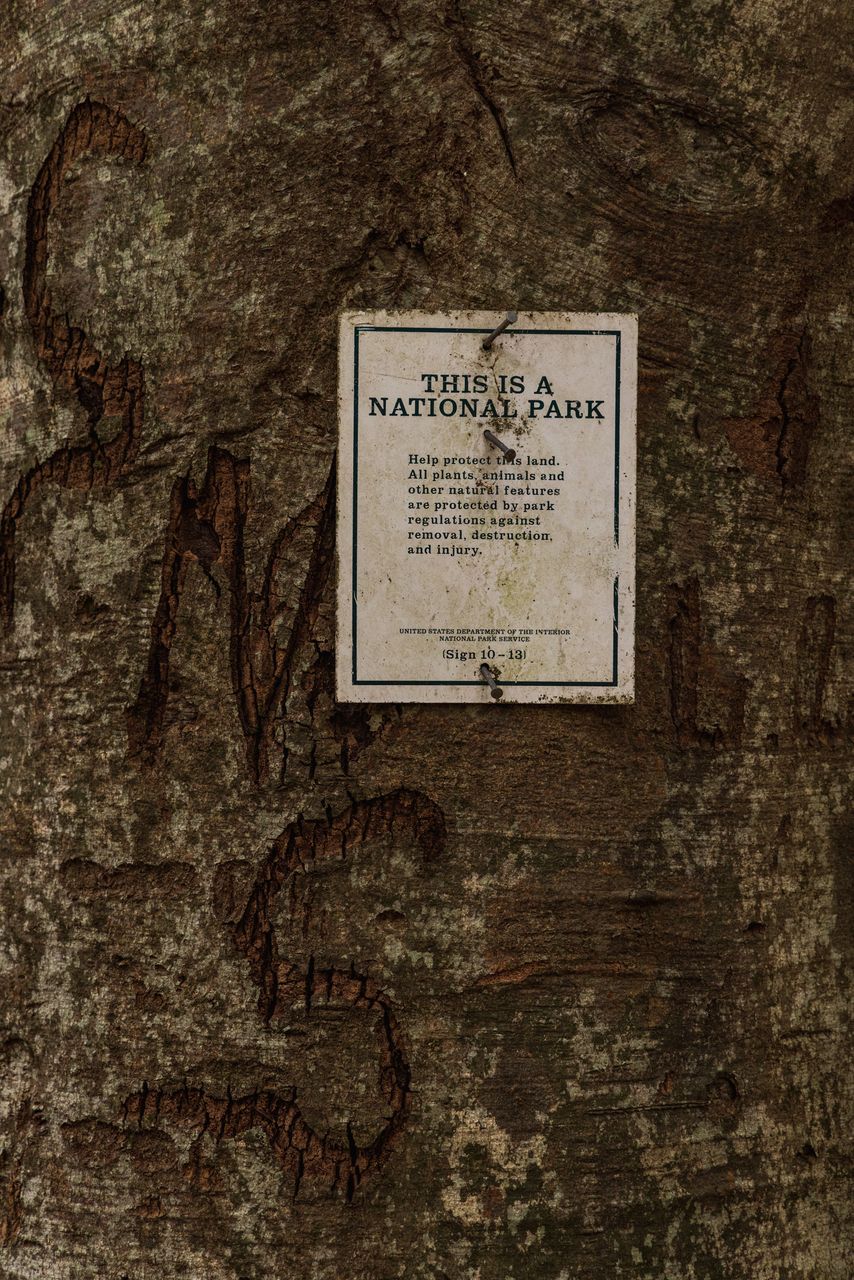

The Natchez Trace Parkway is a 444-mile scenic roadway connecting Natchez, MS to Nashville, TN, with33 miles passing through the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area. After portions of the Old Trace fell out of use and into disrepair, the route was reestablished as a part of the National Park Service in 1938. The construction process was a long one. Construction of the bridge over the Tennessee River, which connects Lauderdale and Colbert counties was not finished until in 1964, and the parkway itself was not completed until 2005.

Known as the “Queen of the Natchez Trace,” Roane Fleming Byrnes was instrumental in preserving the Old Trace and seeing it designated as a National Park Service site in 1938. In 1935, Byrnes became the president of the Natchez Trace Association, which she served as for more than 30 years. During that time, she spent countless hours writing letters and articles emphasizing the parkway’s importance. On Nov. 9, 1951, the first part of the Parkway opened, 65 miles from Jackson, Mississippi, to Kosciusko, Mississippi.

Today, the parkway is still a connection between population centers and allows modern travelers to explore and discover the history and culture of earlier generations. But the parkway does not follow the exact route of the Old Trace, which still exists in some places as modern roads. For example, in Lauderdale County, County Road 5 grew out of the Old Trace’s route.

The gentle sloping and curving composition of the Natchez Trace Parkway closely follows the original foot passage, and its design pays homage to the way the original overlapping trails aligned as an ancient game migratory route. The route generally traverses the tops of the low hills and ridges of the watershed divides from northeast to southwest.