Pond Spring

The metal bars blocking the driveway are just out of sight from Alabama Highway 20, but the traffic rush is still distinct, whooshing between The Shoals and Decatur. John Griffin, the site director, instructed me to close the gate after I unraveled the heavy chains holding it in place. “We aren’t open to the public right now,” he said when I spoke to him over the phone.

From the front of the house, unseen hammering echoed through the yard and the voices of carpenters carried through the maze of arbitrary porches. Kudzu was draped over the trees that framed the house, like sheets over forgotten furniture. John welcomed me, his enthusiasm only slightly withered by the summer heat, and he immediately let me know that the AC was not working in the house— I was grateful for the bandana in my pocket.

It had been decades since I was on site last; Florence City Schools bussed us over for an elementary school lesson in Alabama history. The furnishings looked familiar, but less chaotic than I remembered. The stories of the Wheeler family’s generational hoarding had me itching to see the attic, despite the sweltering heat.

It had been decades since I was on site last; Florence City Schools bussed us over for an elementary school lesson in Alabama history. The furnishings looked familiar, but less chaotic than I remembered. The stories of the Wheeler family’s generational hoarding had me itching to see the attic, despite the sweltering heat.

The scalding air caught in my throat halfway up the staircase to the third flood. It was organized chaos; the boxes were everywhere but carefully tagged. Most labels indicated the rectangular cartons contained military outfits belonging to General Joseph “Joe” Wheeler. Though I had heard rumors of his daughter’s weakness for chic Parisian dresses, I did not see any.

The family relics spill from the proper attic to the Sherrod house next door. Most of its rooms feel bloated with memories and preservation. The insistence on keeping everything lingered over the dusty floors and pressed on the peeling wallpaper. Maybe it was the heat or so many lifetimes crowded into one space, but it felt oppressive. A cotton gin partially blocked the foyer — a previous caretaker claimed it was an Eli Whitney original. John says it’s more likely a Pratt, given its weight and the proximity of Prattville. Cotton fibers gripped the coarse-hair brushes from long dead hogs. I wondered if anyone had consciously recognized the day this contraption would last be used, or if it was gradually forgotten. But 200 years later, it still sits there.

Wheeler was a significant figure in America’s story, known for his roles in the Confederate Army during the Civil War and later in the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War. His life at Pond Spring and his estate in Wheeler are central parts of his legacy, and the history of his immediate family is intertwined with this location.

Born in Augusta, Georgia, on September 10, 1836, he attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1859. Wheeler joined the Confederate Army in 1861, serving primarily in the Western Theater. He became known as one of the South’s most effective cavalry commanders, earning the nickname “Fighting Joe.”

The estate known as Pond Spring, or the Joseph Wheeler Plantation, is in unincorporated Wheeler, in what is now Lawrence County. The estate originally belonged to his wife, Daniella Jones Sherrod Wheeler, whom he married in 1866. The original house, built by Daniella’s father, was a two-room dogtrot cabin still on site. It is whitewashed today, and the breezeway separates two large rooms with open corners that hold mud dauber nests, mounted overhead and buzzing like the pipes of a dirty organ. It is hard to imagine building a life — or a legacy— in only two rooms, but it has been done for millennia.

The estate known as Pond Spring, or the Joseph Wheeler Plantation, is in unincorporated Wheeler, in what is now Lawrence County. The estate originally belonged to his wife, Daniella Jones Sherrod Wheeler, whom he married in 1866. The original house, built by Daniella’s father, was a two-room dogtrot cabin still on site. It is whitewashed today, and the breezeway separates two large rooms with open corners that hold mud dauber nests, mounted overhead and buzzing like the pipes of a dirty organ. It is hard to imagine building a life — or a legacy— in only two rooms, but it has been done for millennia.

The Sherrod House replaced the original dogtrot structure. It sits just west and slightly behind the larger house, and it is a classic early American Greek Revival with white clapboard and two columns framing the front door; a series of covered walkways connects it to the larger house. The “new” house was built in 1888 and was thought to be where the women lived after the family outgrew the “old” house. Despite being constructed in the Victorian era, it has simple architecture and details without many flourished features. There is a wide central hallway downstairs and up, with a front and back room coming off each side.

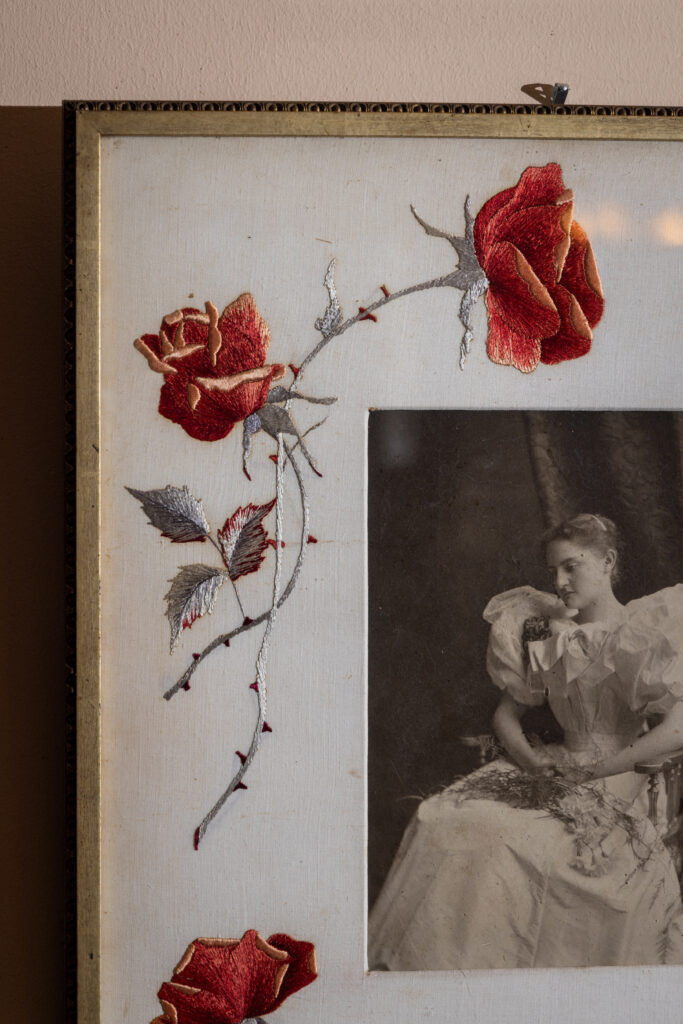

My footsteps echoed on the wide wooden planks outside the downstairs parlors. I spotted several photos framed with fabric matting. One of the Wheeler daughters – though who is lost to time – spent hours carefully embroidering flowers onto the delicate material encircling the familial silhouettes.

My footsteps echoed on the wide wooden planks outside the downstairs parlors. I spotted several photos framed with fabric matting. One of the Wheeler daughters – though who is lost to time – spent hours carefully embroidering flowers onto the delicate material encircling the familial silhouettes. Despite the yellowing of the cloth, the flowers are still distinctly sunny. Similarly, a worn but vibrant needlepoint carpet still covers the floors in the rooms on the east side of the house. John confirmed this carpet has been in place since its installation, presumably around the time the house was completed.

Despite the yellowing of the cloth, the flowers are still distinctly sunny. Similarly, a worn but vibrant needlepoint carpet still covers the floors in the rooms on the east side of the house. John confirmed this carpet has been in place since its installation, presumably around the time the house was completed.

Wheeler and Daniella had several children, including three who survived to adulthood: Lucy Louise Wheeler, Annie Early Wheeler, and Joseph Wheeler Jr. The family was well-regarded in the area, and Pond Spring became a social and agricultural center under their stewardship.

After the Civil War, Wheeler served as a U.S. Congressman from Alabama for several terms (1881-1883 and 1885-1900). His political career was marked by efforts to reconcile the post-war South with the North. In 1898, Wheeler rejoined the U.S. Army as a major general to fight in the Spanish-American War, serving in Cuba. His return to military service for the United States after his Confederate service was highly symbolic of national reconciliation.

Wheeler spent his later years at Pond Spring, remaining active in agricultural and community affairs. He died on January 25, 1906, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery—a rare honor for a former Confederate general.

The Wheeler family home at Pond Spring has been preserved as a historic site and is managed by the Alabama Historical Commission. The estate includes the main house, several outbuildings, and the family cemetery where Daniella and other family members are buried.

Two of the most well-known children are Joseph Wheeler Jr. (1872-1898), Wheeler’s only surviving son, and Annie. Joe Jr. followed in his father’s military footsteps — serving in the Spanish-American War — and died at Pond Spring in 1938. Annie played a significant role in preserving her family’s legacy and the Pond Spring estate. Born on July 31, 1868, Annie was deeply influenced by her family’s history and the values of duty and service to her community and her country — and the world — that her father embodied.

Annie grew up at Pond Spring, surrounded by the history of her father’s military career and the plantation’s operations. The estate was a hub of social and agricultural activity in the region, and Annie was involved in its daily life from a young age. The property was hundreds of acres and stretched to the Tennessee River.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Annie followed in her father’s footsteps of service by volunteering with the American Red Cross. She was a nurse in Cuba, where her father and brother were stationed, and her wool uniform hung over the back parlor as a testament to her service alongside her father’s. Annie was known for her dedication to the soldiers, providing care and comfort to the wounded and sick. Annie’s service during the war was highly regarded, and her efforts earned her widespread admiration.

I believe her time in Cuba is where her desire to travel originated. She particularly loved Japan and brought home many curated souvenirs — from porcelain dishes to silk kimonos. One of the upstairs rooms of the old house is lined with trunks that have initials stamped in block print. The canvas and leather clings precariously to the suitcase frames, but they still incite a sense of agelessness. Standing in front of them, I sensed a personified awareness; they were waiting to be packed and taken on another adventure.

After the deaths of her mother in 1896 and her father in 1906, Annie became the primary caretaker of Pond Spring. She managed the estate’s day-to-day operations, including overseeing agricultural activities, maintaining the house and grounds, and preserving her family’s legacy. Annie was deeply committed to protecting and sharing the history of her father and the Wheeler family. She maintained the family archives, documents, and memorabilia that have become crucial to present-day archivists for historical research. Her efforts ensured that Pond Spring remained a site of historical significance.

I stood at an upstairs window staring down at the skeleton of her gardens. John and I agreed that some extremity of the weather — either frost or heat — had likely killed most of the hedges. He pointed out the etchings on the undulating lead window pane, and my eyes shifted focus. A date was carved there which John said was likely done with a diamond ring. It was a common tradition at the time to verify the stone’s legitimacy and had the additional effect of verifying one’s suitor.

Beyond her work at Pond Spring, Annie was actively involved in local community affairs. She participated in various social and civic activities, continuing the tradition of public service that her family was known for. Annie never married, dedicating her life to her family, the Pond Spring estate, and the community. Her work with the Red Cross did not end with the Spanish-American War; she also served during World War I, continuing her commitment to helping others. Annie Wheeler died on March 10, 1955, at 86. She was buried in the family cemetery at Pond Spring, just out of view from her bedroom.

From the back porch, I spotted an overgrown flagstone path sandwiched between massive boxwood hedges leading away from the house. The walkway gradually opened to a clearing where the family cemetery is located. The stone markers rose in the distance and loomed above a failing iron fence. A historical sign near the entrance indicates that beyond the south wall is a slave cemetery — but without any markers, visitors may not immediately recognize it as a graveyard. The blank spot was pitted by the forgotten dead and I wished I could read their names as well.

The site’s original settlers (the Hickman family) brought 56 enslaved African Americans with them to Pond Spring. Gradually, those enslaved men and women built a community. They constructed houses, a school, and a church south of the main house, towards the Tennessee River. But the scant remains of this settlement’s presence on the landscape — toppled brick piles where buildings once stood —are in silent contrast to the two large Wheeler houses loaded with family heirlooms.

The gravel crunched under my tires back to the gate. I drove into the sun with a bizarre sense of incomprehension– I had accessed the hidden spaces of a family’s most private refuge. And despite that intimacy, I would never hear Miss Annie’s laughter ricochet off the solid walls or recognize the footfalls of General Wheeler on the heart pine. The excited stories of heroism and love drifting over the gravestones and above the boxwoods are quiet. Those things that cannot be contained, held, or boxed—preserved— are the often most meaningful.

Wheeler’s descendants donated Pond Spring to the state of Alabama and the Alabama Historical Commission in 1994. The Joseph Wheeler Plantation was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. Pond Spring is undergoing heavy renovations and is not open to the public as of late 2024. ###

“Pond Spring” text by Zachary Aaron, a historic consultant with the Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area. He is the creator and curator of the @alabamahouses Instagram account, which features historic houses around Alabama. His documentarian work has been recognized by AL.com and Travel + Leisure magazine.

Photos by Abraham Rowe, a Florence photographer who owns and manages digital and film studio Abraham Rowe Photography with his wife, Susan. They work with weddings, musicians, designers and businesses to help tell authentic stories and showcase unique visions.